One thing that most of us consider ourselves to be experts at is watching the TV. We all have our favourite shows to watch, and we’d bet that some of you have said, “This is what they should’ve done”. Well, why not write your own script or screenplay? Fortunately, we have one of the best in the business to advise you, and it’s the Emmy-nominated Matt Witten who’s compiled a guide for us on TV writing.

Would you like to know a great trick for figuring out who the killer is on a TV cop show? If so, read on. If not, skip the following paragraph. Because this paragraph will be a spoiler for about half of the cop shows you watch.

If there is a superfluous character in the first twenty minutes of the show, that character will turn out to be the killer.

See, here’s the thing. In almost all cop shows, like almost all mystery novels, the killer is introduced early on. When the writer doesn’t introduce the killer early enough, then the solution to the murder at the end of the TV show or novel doesn’t feel satisfying. It feels like the killer came out of left field.

But sometimes, it’s hard to get the killer into those first twenty minutes. It doesn’t come naturally, and you have to shoehorn them in there. Hence the phenomenon of the superfluous character.

You know the character I mean. When the detective meets with the murdered man’s wife and his sister-in-law is hovering in the background making tea, you can bet your bottom dollar that the sister-in-law is the killer. When the detective knocks on the door and the suspect’s son answers and calls upstairs for the suspect to come down, then goes off to his room and disappears from the scene, guess who the killer is? Right: the son.

Another fun thing to look for in cop shows: what the staff on my first TV show, Law & Order, called “the boo-hoo scene.” That’s the scene, usually in the first fifteen minutes, where the murder victim’s husband or best friend or whatever starts crying about how she was such a great person and everyone loved her. Writers throw that scene in to make sure the audience cares about the victim. Because if we don’t care, we change the channel.

Often victims in TV shows get killed in part because they were having an affair or cheating somebody out of money, or doing something else shady, so it’s useful to have somebody early on in the show basically testifying that the victim was a worthy person deserving of our sympathy, and justice.

So if you’re thinking of writing a spec TV pilot for a crime show, keep these things in mind: introduce your killer early, and make sure we care about the victim early.

Here’s another fun TV writing technique that I learned early on in my career writing for crime dramas like Law & Order, CSI: Miami, Pretty Little Liars, Medium, The Glades, Peacemakers, and Women’s Murder Club. When a homicide investigator goes to a location looking for something, or someone, he never finds it; he finds something else.

So, for instance, if Detective Garbanzo goes to the bar and asks, “Was Joe here the night of the murder?”, the answer is always no. But then the bartender, or waiter, will add, “But Joe’s wife was here.” Aha! Now the detective has a whole new direction to go in.

When TV writers follow this basic rule, the show seems twisty and fun. If the writers get lazy and the answer to the detective’s question is, “Yes, Joe was here…” Well, that’s where the show starts to feel a little slow, and you check your phone for messages.

Also, in every investigative scene, ideally, the detective finds something. Because if they find nothing, then what was the point of the scene?

I believe this principle – that if a main character goes to a location looking for A, they never find A, but they find B – applies to non-crime shows as well. For instance, in a soap opera or sitcom, if a character goes to someone’s house hoping for a kiss, they don’t get a kiss: maybe they get a whack in the face, maybe they get something even more exciting than a kiss, but they don’t get just a simple kiss.

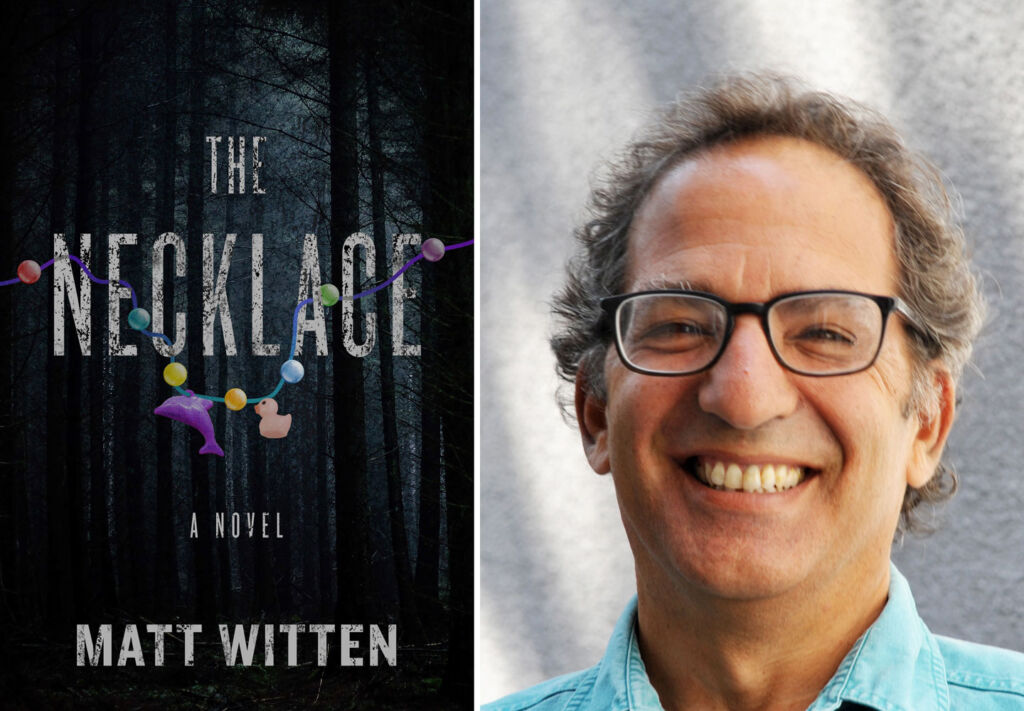

I teach TV writing at UCLA, and I’ve run into students from twenty years ago who mention that they still remember this principle and use it. When writing my thriller novel The Necklace, about a middle-aged woman who believes that the man about to be executed for killing her daughter is actually innocent, I tried to keep this principle in mind at all times. I believe it’s one reason why the novel feels twisty.

For those of you who are contemplating writing a spec TV pilot, or screenplay, I’ll offer one more word of wisdom that I’ve found very helpful, that I learned from the head writer of the TV show House. No matter what you’re writing – drama or sitcom, movie or novel – ideally, almost every scene should both advance the plot – help solve the murder, say – and also reveal character and advance the characters’ personal stories.

If you’re writing a teleplay or screenplay, good luck! And for everyone else, I hope you’re able to amaze your friends with your newfound ability to guess who the killer is on cop shows.

The Necklace: A Grieving Mother’s Quest for Justice by Matt Witten is out in paperback, priced at £8.99, published by Legend Press.

Read Matt Witten’s guide to writing a novel here.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.